You know how some jerks like to say that women aren’t funny? It turns out that falsehood has been around for some time — perpetuated, for example, by many nineteenth-century reviewers and anthologists. Alfred H. Miles wrote in 1897 that it is a “contention often made that women are distinctly lacking in a sense of humour” (613). (Spoiler alert: he agreed.) And when reviewers wrote of nonsense poet May Kendall, they noted her “rare gift of humour—a quality not always present in the gentler sex” (“Recent” 27).

So yeah. Jerks.

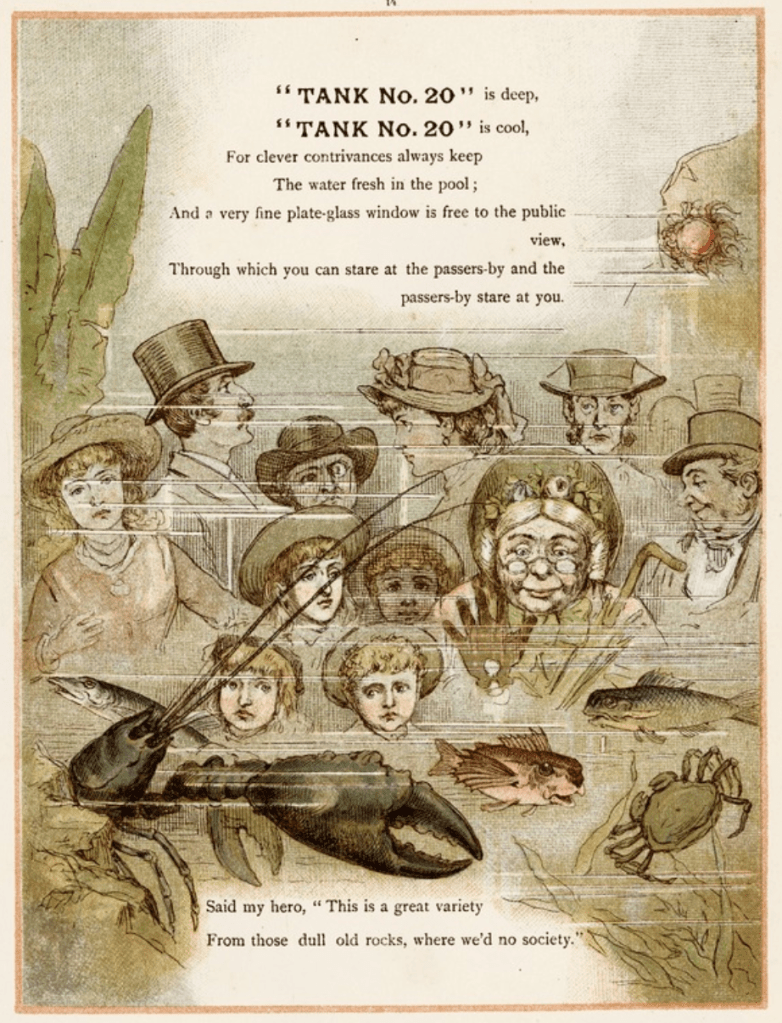

I write about May Kendall and other witty Victorian female poets — especially Christina Rossetti and Juliana Horatia Ewing — in one my of latest publications: an entry on nonsense poetry The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Victorian Women’s Writing. One of my favorite things about this short piece? It let me think about the intersections of nineteenth-century science and poetry, including this amazing piece published in Punch in 1888:

Palgrave Encyclopedia of Victorian Women’s Writing is edited by Lisa Scholl and Emily Morris. It is available online (and soon in print, as well). Contact me if you don’t have access and would like to read my entry!

Works Cited

Miles, Alfred H. The Poets and Poetry of the Century, Vol. 9: Humour, Society, Parody, and Occasional Verse. Hutchinston, 1894.

“Recent Poetry and Verse.” Graphic, issue 947, 21 January 1888, p. 27.