I recently submitted a first draft of an essay on Victorian women nonsense poets. Writing it a challenge because, as it turns out, there aren’t many. I asked around in the hopes of crowd-sourcing, and most of my Victorianist friends would name Christina Rossetti’s Sing-Song: A Nursery Rhyme Book and then grow quiet, staring thoughtfully into the middle distance.

I would sometimes join them, but it turns out there are not any Victorian women nonsense poets residing in the middle distance. I did, however, appreciate revisiting Sing-Song. While most making the case that it’s nonsense refer to the verse that begins “If a pig wore a wig,” I prefer this one:

Thank you, Arthur Hughes, for illustrating a lizard using its tail as a sassy scarf.

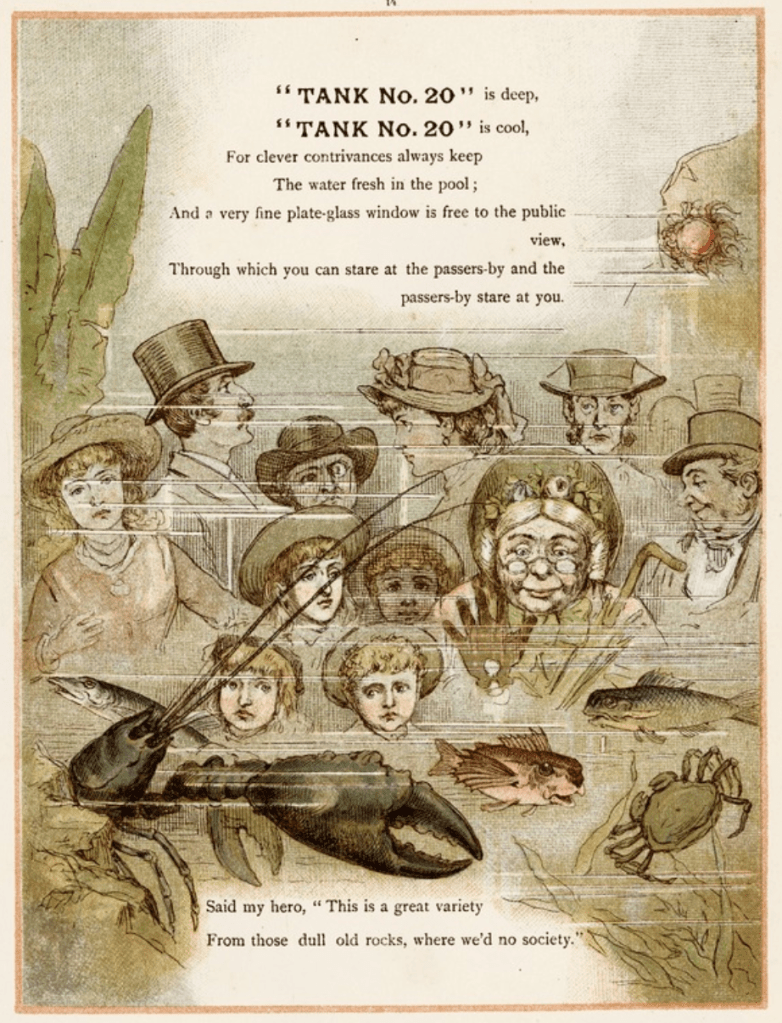

One of my oddest finds during this particular research project was Blue and Red, or, The Discontented Lobster, a long comic poem of the “grass-is-always-greener” variety that was published first in Aunt Judy’s Magazine in 1881 and two years later by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge as a toy book illustrated by Richard André. The titular lobster, who possesses an admirable blue shell and a sulky attitude, is caught and displayed in an aquarium, where he observes the vivid vermillion shells of a different species. He longs to be red, and his wish is granted when he is discovered by a chef. As the narrator laments,

It seems to me a mean end to a ballad,

But the truth is, he was made into a salad;

It’s not how one’s hero should end his days,

In a mayonnaise.

I’ve been a Ewing fan for some time, but this is the first time I’d encountered André, whose illustrations are a little uneven but occasionally really delightful. One of my favorites depicts the lobster’s view of passerby — an image that situates the reader behind the lobster, suggesting the claustrophobic (to me) or delightful (to the lobster) status of the looked-at.

And then there is André’s depiction of the lobster’s moment of greatest discontent, in which he stares longingly at his future undoing, the reader powerless to explain the grim reality of a red shell: